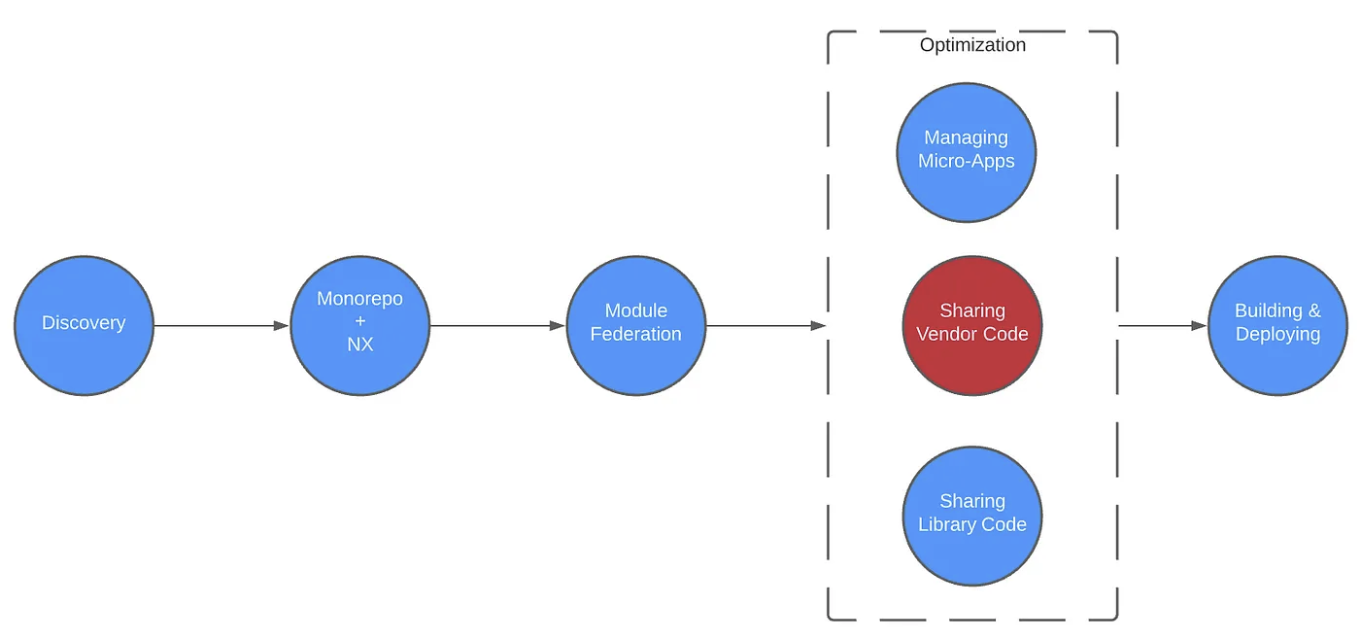

Module Federation — Sharing Vendor Code

This is post 2 of 9 in the series

- Introduction

- Why I Implemented a Micro Frontend

- Introducing the Monorepo & NX

- Introducing Module Federation

- Module Federation — Managing Your Micro-Apps

- Module Federation — Sharing Vendor Code

- Module Federation — Sharing Library Code

- Building & Deploying

- Summary

Overview

This article focuses on the importance of sharing vendor library code between applications and some related best practices.

The Problem

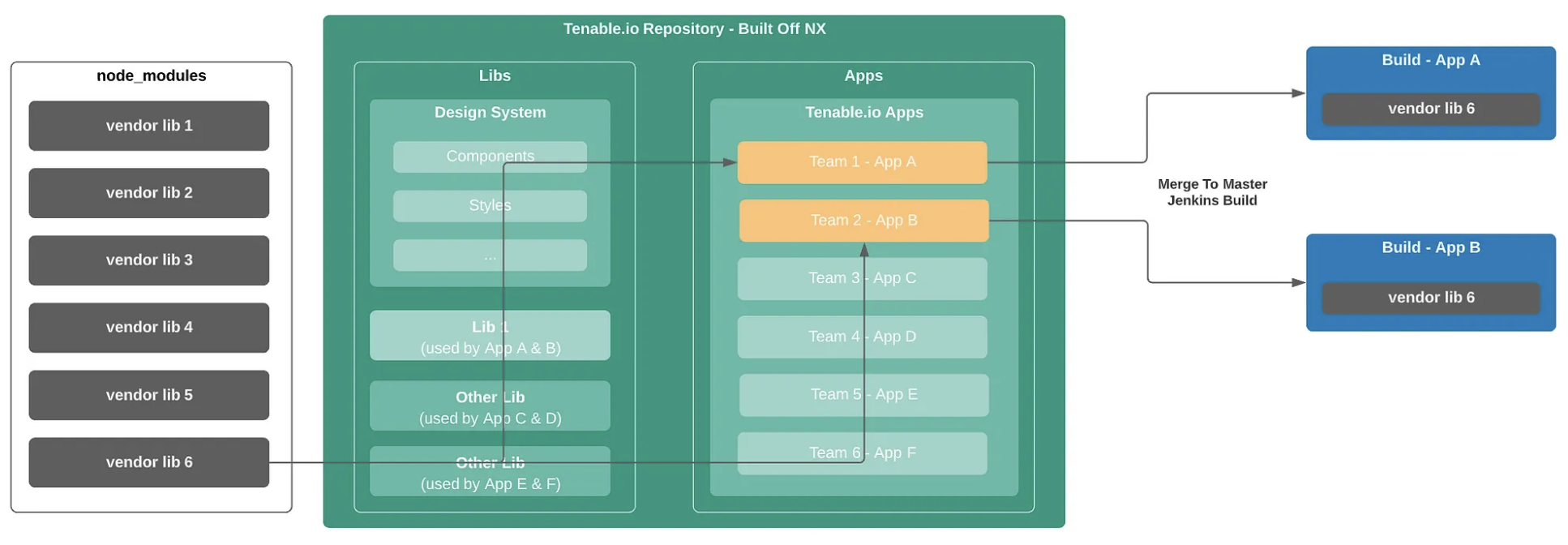

One of the most important aspects of using module federation is sharing code. When a micro-app gets built, it contains all the files it needs to run. As stated by webpack, “These separate builds should not have dependencies between each other, so they can be developed and deployed individually”. In reality, this means if you build a micro-app and investigate the files, you will see that it has all the code it needs to run independently. In this article, we’re going to focus on vendor code (the code coming from your node_modules directory). However, as you’ll see in the next article of the series, this also applies to your custom libraries (the code living in libs). As illustrated below, App A and B both use vendor lib 6, and when these micro-apps are built they each contain a version of that library within their build artifact.

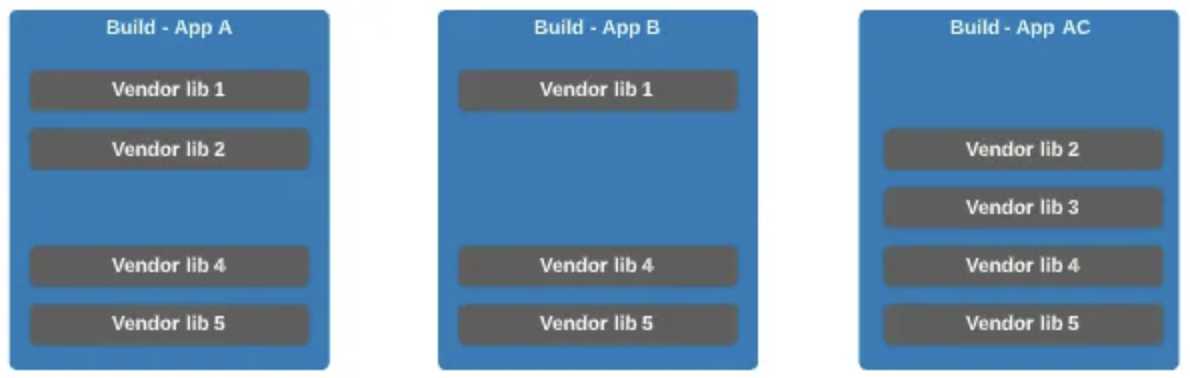

Why is this important? We’ll use the diagram below to demonstrate. Without sharing code between the micro-apps, when I load in App A, it loads in all the vendor libraries it needs. Then, when I navigate to App B, it also loads in all the libraries it needs. The issue is that we’ve already loaded in a number of libraries when I first loaded App A that could have been leveraged by App B (ex. Vendor Lib 1). From a customer perspective, this means they’re now pulling down a lot more Javascript than they should be.

The Solution

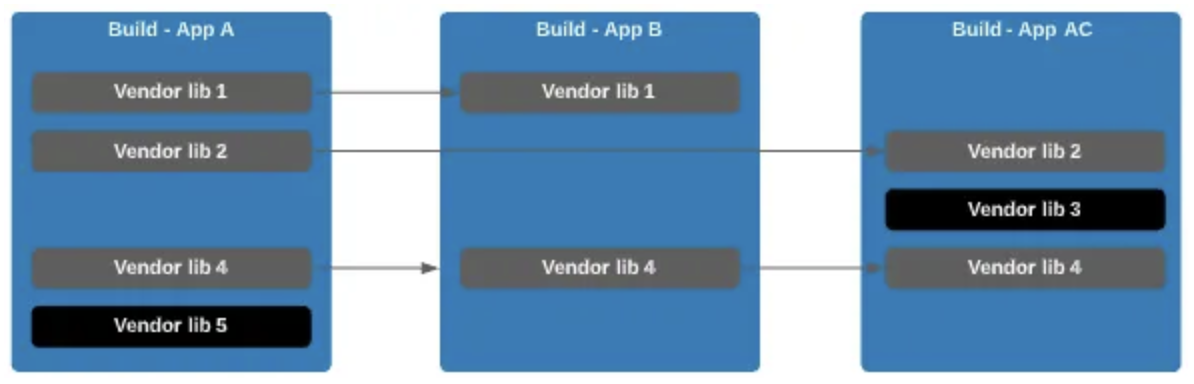

This is where module federation shines. By telling module federation what should be shared, the micro-apps can now share code between themselves when appropriate. Now, when I load App B, it’s first going to check and see what App A already loaded in and leverage any libraries it can. If it needs a library that hasn’t been loaded in yet (or the version it needs isn’t compatible with the version App A loaded in), then it proceeds to load its own. For example, App A needs Vendor lib 5, but since no other application is using that library, there’s no need to share it.

Sharing code between the micro-apps is critical for performance and ensures that customers are only pulling down the code they truly need to run a given application.

Diving Deeper

Before You Proceed: The remainder of this article is very technical in nature and is geared towards engineers who wish to learn more about sharing vendor code between your micro-apps. If you wish to see the code associated with the following section, you can check it out in this branch.

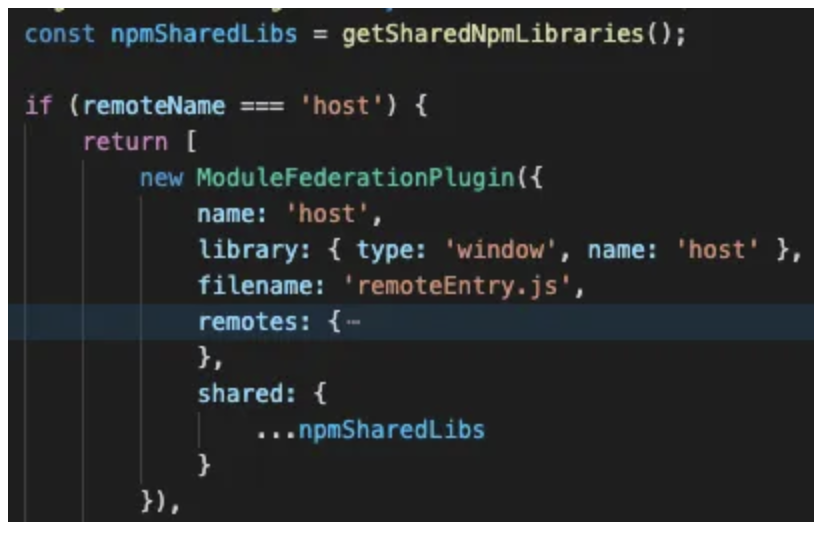

Now that I understand how libraries are built for each micro-app and why I should share them, let’s see how this actually works. The shared property of the ModuleFederationPlugin is where you define the libraries that should be shared between the micro-apps. Below, I are passing a variable called npmSharedLibs to this property:

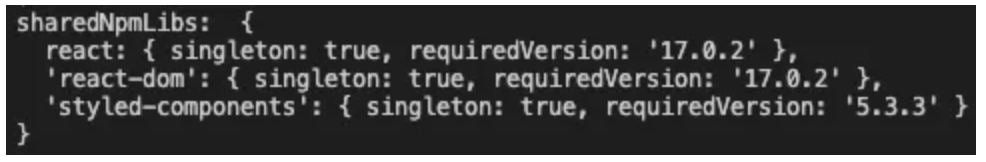

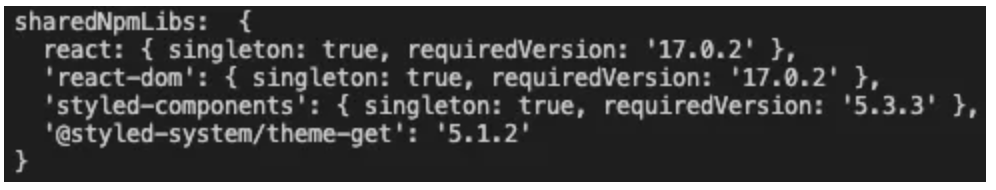

If I print out the value of that variable, we’ll see the following:

This tells module federation that the three libraries should be shared, and more specifically that they are singletons. This means it could actually break our application if a micro-app attempted to load its own version. Setting singleton to true ensures that only one version of the library is loaded (note: this property will not be needed for most libraries). You’ll also notice I set a version, which comes from the version defined for the given library in our package.json file. This is important because anytime I update a library, that version will dynamically change. Libraries only get shared if they have a compatible version. You can read more about these properties here.

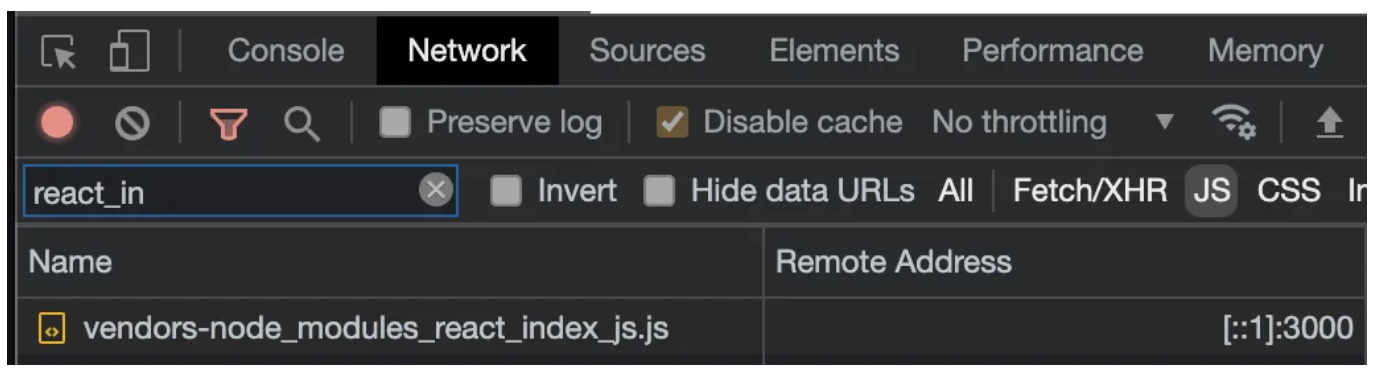

If I spin up the application and investigate the network traffic with a focus on the react library, we’ll see that only one file gets loaded in and it comes from port 3000 (our Host application). This is a result of defining react in the shared property:

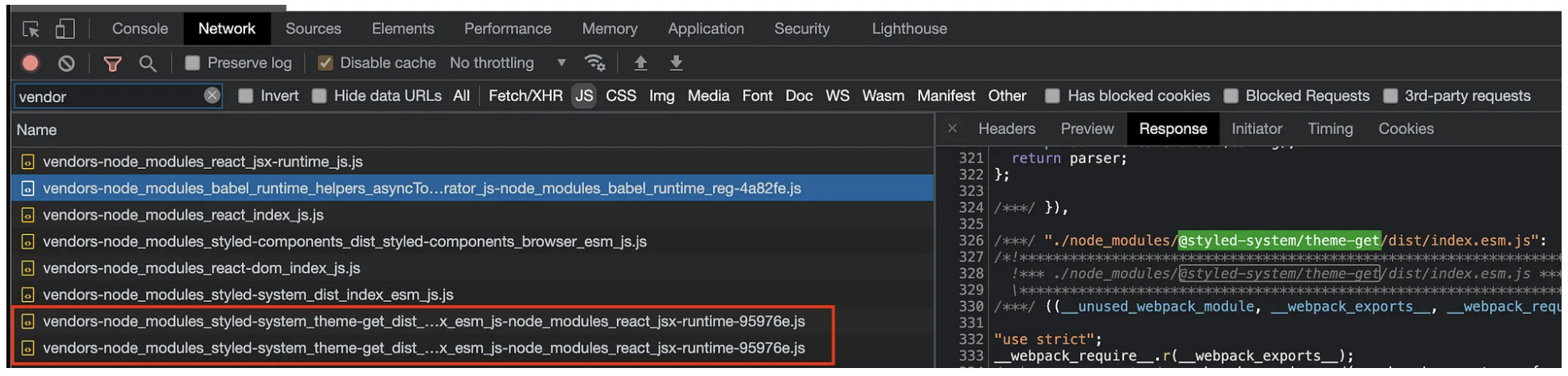

Now let’s take a look at a vendor library that hasn’t been shared yet, called @styled-system/theme-get. If I investigate our network traffic, we’ll discover that this library gets embedded into a vendor file for each micro-app. The three files highlighted below come from each of the micro-apps. You can imagine that as your libraries grow, the size of these vendor files may get quite large, and it would be better if I could share these libraries.

I will now add this library to the shared property:

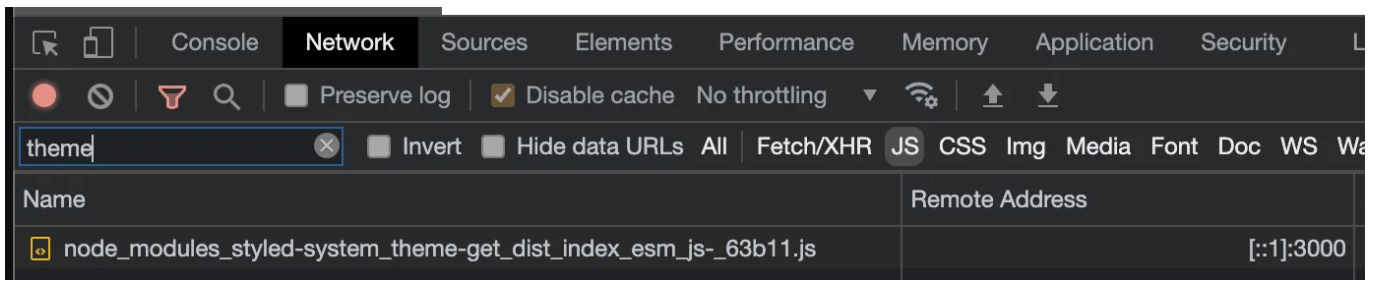

If I investigate the network traffic again and search for this library, we’ll see it has been split into its own file. In this case, the Host application (which loads before everything else) loads in the library first (I know this since the file is coming from port 3000). When the other applications load in, they determine that they don’t have to use their own version of this library since it’s already been loaded in.

This very significant feature of module federation is critical for an architecture like this to succeed from a performance perspective.

Summary

Sharing code is one of the most important aspects of using module federation. Without this mechanism in place, your application would suffer from performance issues as your customers pull down a lot of duplicate code each time they accessed a different micro-app. Using the approaches above, you can ensure that your micro-apps are both independent but also capable of sharing code between themselves when appropriate. This the best of the both worlds, and is what allows a micro-frontend architecture to succeed. Now that you understand how vendor libraries are shared, I can take the same principles and apply them to our self-created libraries that live in the libs directory, which I discuss in the next article of the series.